Medical adhesives are an exciting emerging technology for wound closure and medical device fixation. Adhesives offer advantages over traditional fixation methods (e.g. sutures and staples), including immediate and secure application, non-traumatic closure, and elimination of fixation removal.[1] Acrylate based adhesives have found application as bone[2] and dental cement (methacrylate, MA), as well as liquid sutures (cyanoacrylate, CA).[3] These materials cure quickly and accurately, and in the case of CA offer superior cosmetic closure. Unfortunately, a small but significant number of patients are sensitive to these acrylate materials,[4] and the monomers can exhibit significant toxicity due to their reactivity.[5]

Here, I present a strategy to improve the compatibility and add therapeutic value to acrylate-based adhesives. Using chemical bonds that can be predictably cleaved in physiological conditions, we can modify acrylate monomers to reduce their toxicity and incorporate elements for controlled release and/ or to signal appropriate healing. These materials offer promise of a convenient method of closure or fixation that will result in faster, directed healing and less pain. Using knowledge of carbonyl chemistry, we can selectively deliver the desired therapeutic in a predictable manner. Anhydride bonds are hydrolytically unstable, and degrade quickly in the aqueous environment encountered in the body. This bond can be quickly degraded to deliver the payload in a burst release fashion. Ester bonds degrade more slowly and offer a sustained release. Finally, amide bonds are relatively stable under physiological conditions, so the amide bond could be used to attach signaling moieties that are beneficial directly at the tissue-biomaterial.

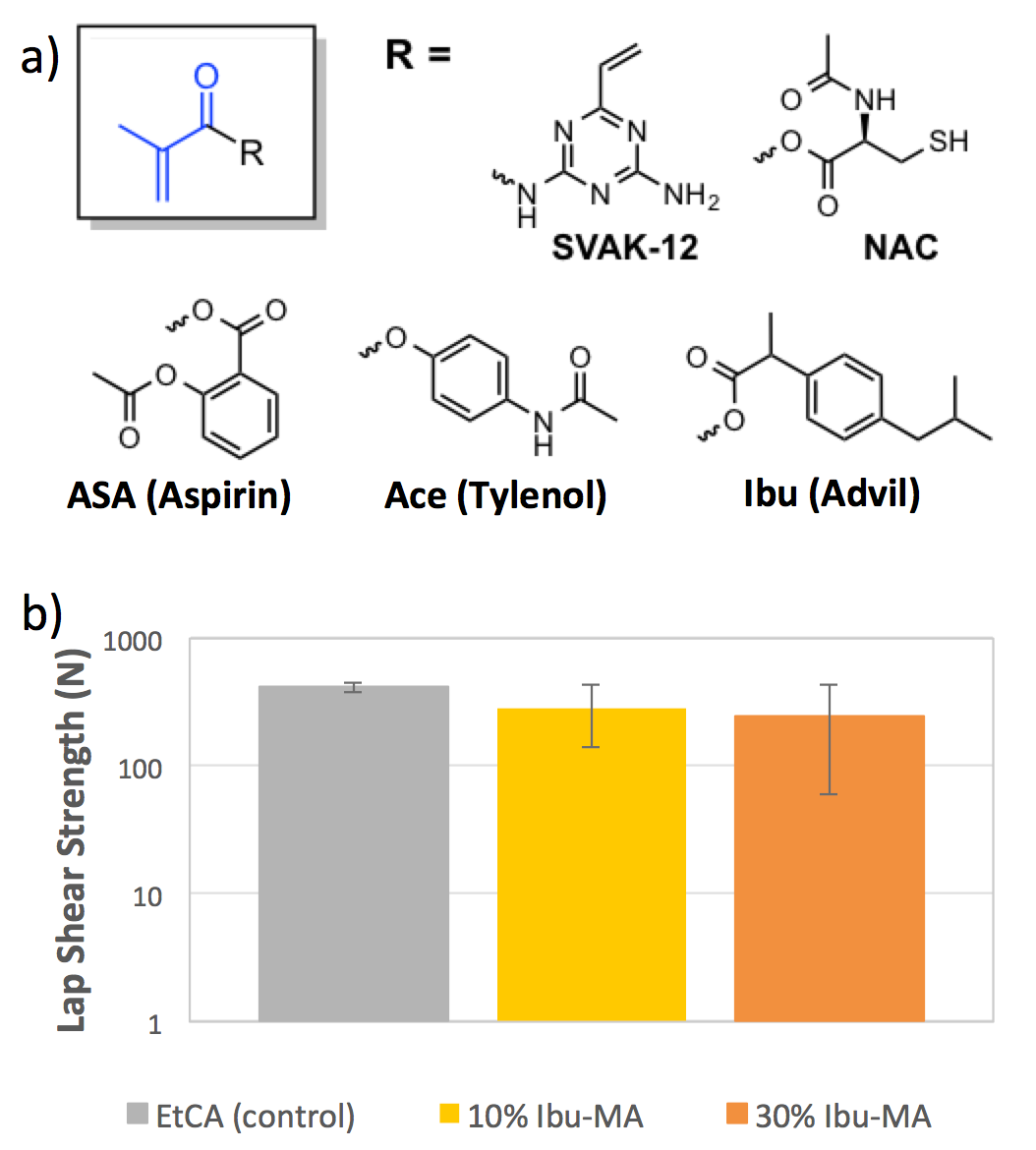

In one example, we attach ibuprogen to methacrylate via an anhydride bond (Ibu-MA, Figure 1a) and blend this with commercially available cyanoacrylate adhesives, such as 3M’s VetBond ™ at 10 and 30 weight % does not significantly alter the lap shear strength of the bond (Figure 1b). Further studies are underway to verify that the adhesive strength transfers to tissues. Despite the lower reactivity of the methacrylate in comparison to the cyanoacrylate, the gel time for these therapeutic adhesives are comparable or faster than that of the commercial cyanoacrylate alone. Most notably, however, we are able to observe release of the ibuprofen payload ex vivo over 72 hours in a preliminary study. Further work is underway to determine the in vitro compatibility of the adhesive andmonomers. We expect that the bulkier, therapeutic side chains will enhance the biocompatibility.

In summary, we are developing a new class of acrylate adhesive that can deliver therapeutic moieties at the site of injury. These monomers seamlessly integrate with FDA approved acrylate adhesives, such as 3M’s VetBond™ and offer promise for improved compatibility and flexibility. We are excited about these findings and think that these adhesives offer promise for better biocompatibility and the next generation of medical adhesives.

References:

[1] Duarte, A. P., Coelho, J. F., Bordado, J. C., Cidade, M. T. & Gil, M. H. Surgical adhesives: Systematic review of the main types and development forecast. Prog. Polym. Sci. 37, 1031–1050 (2012).

[2] Robinson, R. P., Wright, T. M. & Burstein, A. H. Mechanical properties of poly(methyl methacrylate) bone cements. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 15, 203–208 (1981).

[3] Grimaldi, L. et al. Octyl-2-cyanoacrylate adhesive for skin closure: eight years experience. Vivo Athens Greece 29, 145–148 (2015).

[4] Drucker, A. M. & Pratt, M. D. Acrylate contact allergy: patient characteristics and evaluation of screening allergens. Dermat. Contact Atopic Occup. Drug 22, 98–101 (2011).

[5] Autian, J. Structure-toxicity relationships of acrylic monomers. Environ. Health Perspect. 11, 141–152 (1975).